Click each numbered icon on the images below to read about different parts of the tobacconist’s sign and its original museum label.

CONTENT WARNING

The Museum of Cambridge’s collection features objects connected with Britain’s colonial history. These objects are associated with histories of enslavement and colonial violence. Some objects and past labels may feature inaccurate, racist, or otherwise inappropriate imagery and content. These past labels often may not yet adequately address objects’ colonial histories. Some visitors may find these objects and labels insensitive, disturbing, or even traumatising. The museum has begun to address harmful legacies of its collections through the new ReStorying OUR Museum pilot project. We welcome your feedback or suggestions, which you may send to enquiries@museumofcambridge.org.uk.

Tobacconist’s Sign – 18th Century

What’s in a tobacco shop sign?

What’s in a tobacco shop sign?

A tobacconist is a person or business selling tobacco products and related goods, like pipes and matches.

English shopkeepers in the 1700s often had decorative wooden signs made to advertise their trades using imagery that would have been familiar to people at the time. According to the Museum of Cambridge’s original label for this tobacconist sign, it is thought to portray an African figure (left) and a Turkish figure (right) on either side of barrels of tobacco leaves. Such signs and other tobacco advertising often emphasised tobacco’s “New World” associations and its foreign use to market tobacco as “exotic.”

This sign was donated to the museum in 1946 and is on display in the guest room upstairs.

Where in the world?

Where in the world?

The Origins of Tobacco

These leaves represent tobacco, the product advertised by this sign.

For thousands of years, diverse Indigenous peoples of the Americas traditionally used tobacco for many reasons, especially

- ● for spiritual purposes,

- ● as medicine for various illnesses,

- ● as gifts for visitors,

- ● and for smoking.

The Great Debate

The Great Debate

Did you know that tobacco has spiritual and medicinal significance in some cultures?

Indigenous Americans first held this belief. They introduced tobacco to European colonisers in the late 1400s. Some Europeans believed that tobacco was a God-given medicine. Others thought that tobacco was “the food of the devil” because non-Christians had grown and used it first. A great debate began and lasted for centuries!

Commercial Tobacco and Enslavement Take Root

Commercial Tobacco and Enslavement Take Root

After learning how to grow tobacco from Indigenous Americans, English colonists in Virginia started growing tobacco in the early 1600s and soon began exploiting the labour of enslaved Africans. In the 1700s, wealthy Virginia planters bought tens of thousands of enslaved Africans. Tobacco produced through this brutal practice became a key colonial product, and Virginia tobacco came to dominate the English tobacco market.

Merchants used massive barrels like the ones shown here to ship tobacco to Europe.

![]() Click on icon 8 to learn about experiences of enslavement on colonial tobacco plantations from a firsthand perspective.

Click on icon 8 to learn about experiences of enslavement on colonial tobacco plantations from a firsthand perspective.

Cambridge Tobacco Shops

Cambridge Tobacco Shops

While the Museum of Cambridge has not yet located information about specific local tobacco shops in the 1700s, there were a number of tobacco sellers here later on in central areas of town, including King’s Parade and Sidney, Regent, and Trinity Streets. Some tobacco shops were even neighbours of the White Horse Inn before it became the Museum of Cambridge.

![]() Check out some of their signs in the photographs here and here!

Check out some of their signs in the photographs here and here!

What does Bacon have to do with tobacco?

What does Bacon have to do with tobacco?

One of Cambridge’s oldest known tobacco shops was Bacon Tobacco Manufacturers (1805–1983). In 1862, Cambridge-educated poet Charles Stuart Calverley wrote the humorous “Ode to Tobacco” in its honour. A plaque with this poem still marks one of the former shop’s walls at the corner of Market Square and Rose Crescent. It is a lasting reminder that Cambridge is no stranger to the legacies of British colonialism.

“An African”: Marketing Tobacco as “Exotic,” Masking Colonial Realities

“An African”: Marketing Tobacco as “Exotic,” Masking Colonial Realities

The tobacconist sign’s original museum label describes this figure as “an African slave.”

By the early 1600s, English people had come to associate images of Africans with tobacco and tobacco shops. In the 1700s, London tobacconist signs and advertisements often depicted a “Black Indian” with a crown and clothes made of tobacco leaves. These kinds of images did not acknowledge the industry’s reliance on colonial plantations, let alone accurately portray Western European practices of enslaving Africans to perform the hard manual labour of tobacco growing. Instead, signs like this suggest the tobacco trade involved legitimate exchanges with “exotic” Black rulers. Taking a closer look at these signs can help uncover the troubling reality behind tobacco production and highlight how Black men were seen as inferior.

![]() How do you think this figure is portrayed?

How do you think this figure is portrayed?

A Voice from the Past

A Voice from the Past

After escaping enslavement in Virginia and moving to England, Francis Fredric described his experiences in this excerpt from his book Fifty Years of Slavery in the Southern States of America (1863).

*Readers may find some content disturbing.*

My master had about 100 slaves, engaged chiefly in the cultivation of tobacco, this and wheat being the staple produce of Virginia at that time. The slaves had to work very hard in digging the ground with what is termed a grub hoe. The slaves leave their huts quite early in the morning, and work until late at night, especially in the spring and fall. I have known them very often, when my master has been away drinking, work all night long, husking Indian corn to put into cribs.

![]() You can learn more about Fredric’s difficult experiences here.

You can learn more about Fredric’s difficult experiences here.

Tobacco clothes?

Tobacco clothes?

Do you think this figure’s clothes are made of tobacco leaves or feathers?

It’s hard to say for sure, but many historical tobacco advertisements show stereotypes of figures that inaccurately combine both African and Indigenous American features. For example, some show enslaved Africans wearing feathered clothing and even headdresses. Depicting Africans like “exotic” rulers implied that the colonial tobacco trade involved legitimate exchanges rather than brutal enslavement.

![]() Why are such visual stereotypes problematic?

Why are such visual stereotypes problematic?

“A Turk”: Marketing Tobacco as “Exotic”?

“A Turk”: Marketing Tobacco as “Exotic”?

The tobacco shop sign’s original label describes this figure as “a Turk.” Around 1600, Europeans introduced tobacco to the Ottoman Empire, where it became common for some locals to offer tobacco, along with coffee, to guests. English travel writings and European art came to associate tobacco use in Ottoman coffee houses and palaces, especially in women’s apartments, with sensual indulgence. Though it’s difficult to assess this sign’s intent, its imagery may have been meant to further link tobacco use to “exotic” regions, socialising, and even sensual pleasure.

Where are the women?

Where are the women?

Most customers at English tobacco shops in the 1700s were white men. Meanwhile, enslaved African women and men alike toiled to produce tobacco on plantations in British colonies like Virginia. The imagery on this sign presumably was meant to appeal to white male customers. However, it obscures the role African women played in tobacco production.

As tobacco came to be smoked by and marketed to more women in the 1800s and 1900s, women were featured in more and more tobacco advertisements, where they were often sexualised.

Behind the Sign: Enter the Shop

Behind the Sign: Enter the Shop

What would customers actually find inside an English tobacco shop in the 1700s? Many historical illustrations showcase how the outside of tobacco shops would feature images of Native Americans or African Americans, while inside there would be many well-dressed white men smoking clay pipes. As the words bordering the sign suggest, customers could have purchased either (1) pipe tobacco or cigars for smoking or (2) snuff for ingesting through the nose. All of these forms of commercial tobacco and ways of consuming it had sacred, traditional Indigenous origins.

What do you think?

What do you think?

- ● Can you think of signs or advertisements today that misrepresent or exploit?

- ● What are the implications for the people of Cambridge of having benefitted from colonialism, enslavement, and their legacies?

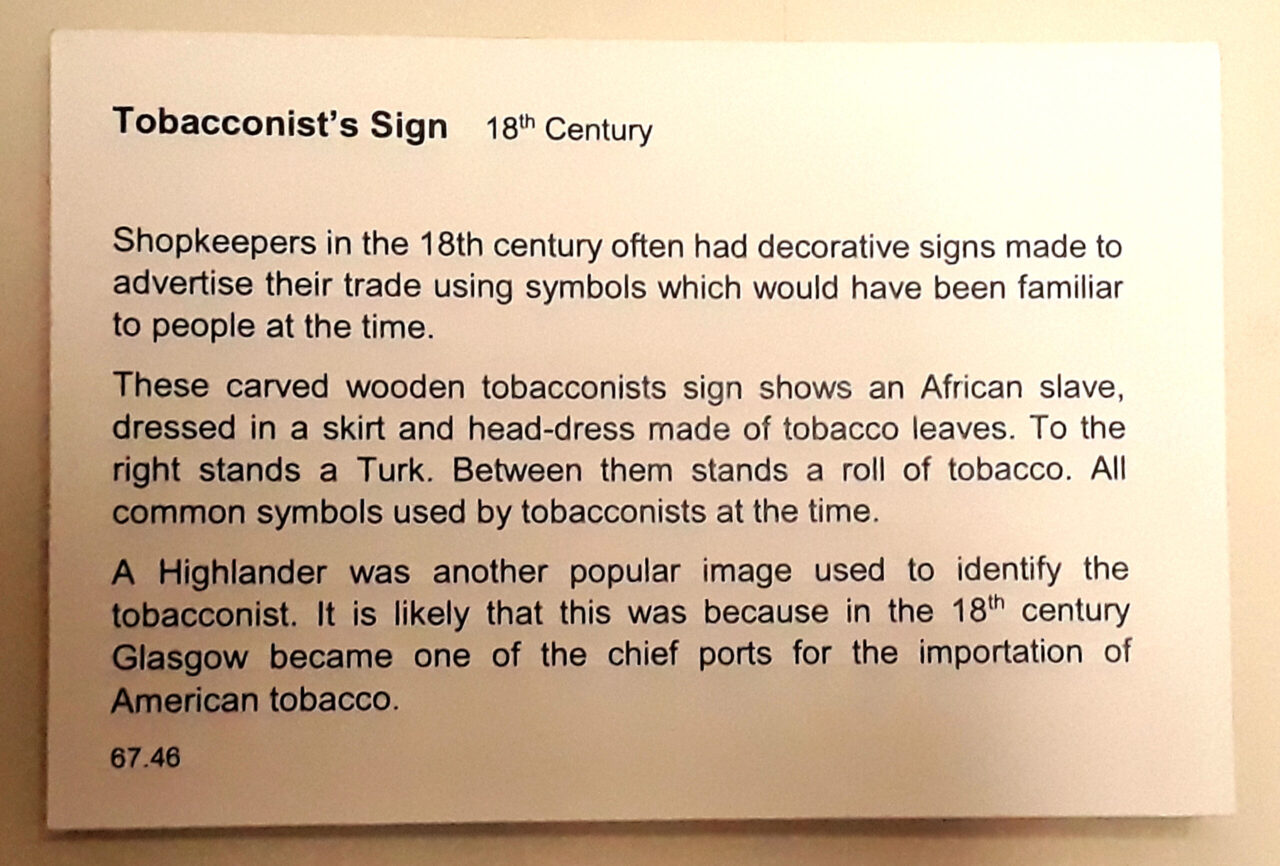

The Museum’s Original Label for the Tobacconist’s Sign

What is (or isn’t) in a label?

What is (or isn’t) in a label?

This is the tobacco shop sign’s original museum label. Participants in the ReStorying OUR Museum project thought that the museum’s original label for the tobacco shop sign was “economical with the truth.” In other words, they believed that the label did not share information about important issues, namely Britain’s colonial past.

For example, participants pointed out that the label

- ● sounds surprisingly neutral and matter-of-fact

- ● makes assumptions about visitors’ previous knowledge

- ● does not give context about tobacco shops in Cambridge

- ● does not acknowledge the role of enslavement and forced labour in tobacco production, which is part of the broader history of colonialism

For references used in the creation of this display, please have a look at our resource library.