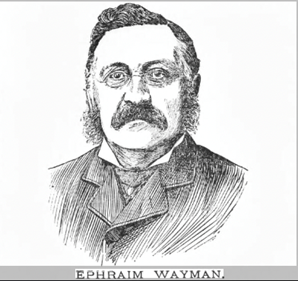

It was an email to Capturing Cambridge earlier this year that uncovered this tragic tale of greed and embezzlement. It revealed family feelings that are still raw today, looking back on the suicide of Anthony Phypers, a well-off and respected farmer of 680 acres from Hatton House, Long Stanton who had been defrauded by the Cambridge solicitor, Ephraim Wayman.

The story started in the newspapers in April 1888. The Cambridge Independent Press had come to hear that Ephraim Wayman was in financial difficulty. Solicitors at that time routinely handled large sums of money to be invested on behalf of their clients; Ephraim was afraid that adverse publicity might embarrass him so he asked the newspaper to wait for him to sort things out before publishing. This gave Ephraim a few days to escape Cambridge, never to return.

The knock-on effects were immediate. The papers reported the clamour at Wayman’s Cambridge office: ‘Numbers of men and women alike have arrived there in a state of the greatest distress to make inquiries respecting their investments and securities, in some cases representing all the property the people possessed. Some of these poor people have been so overcome that they represent themselves as being unable to take their food by day or sleep by night.’ It was discovered that Wayman’s bookkeeping was so chaotic that even his own clerk couldn’t make sense of the figures. It was at this point that the papers reported the sad demise of Anthony Phypers, who had ‘breakfasted as usual with his family this morning, and shortly afterwards was found in a dying condition in the summer-house, with a pint tankard by his side containing a spoon and some liquid which has not yet been analysed.’

By May the full extent of the financial disaster was becoming evident. The Cambridge Independent Press could not keep up with demand for news. ‘So great was that interest that we were compelled to print three extra editions of our journal, and even then we were sold out and unable to completely supply the public demand. The widespread character of the commotion is due to the fact that there are hundreds persons in the town and neighbourhood who have, unfortunately, been more or less involved in Mr Wayman’s failure.’

The same paper went to the lengths of publishing a biography of Ephraim Wayman, such was the interest in his actions and whereabouts. They managed to find a photo since, Wayman being a town councillor, he had been included in an official photo on the occasion of the Queen’s Jubilee. They investigated his childhood in Girton and his relationship with his family, several of whom also suffered in the scandal.

Wayman had trained as a solicitor and opened an office in Free School Lane; it was from this time that he was reported to have become rather fond of the luxuries of life, oysters and wine, and his generosity that meant he became very popular, especially with members of the Conservative Party. He was appointed to special legal roles, such as ‘Perpetual Commissioner for the taking the oaths of married women’, and moved to smarter offices in Silver Street.

He married a Miss Annie Hanchett, daughter of an Ickleton farmer. She was to be abandoned by her husband when disaster struck. In the meantime they became well-known for their parties; she herself was a painter and her own portrait, destined to be sold at the auction of their household goods to recover money for creditors, was painted by the famous Robert Farren. At some point the Waymans went to live at Merton House, Madingley Road; it was reported that while here his income was about £3,000 a year. However the estimate of the losses as a result of his bankruptcy was around £100,000, the equivalent of millions in 2024.

In order to extend his influence further he decided to take a degree at Peterhouse. This was very useful in building bridges with the University authorities since, in 1859, he had been ‘discommuned for a money-lending transaction, in connection with which he obtained a security from an undergraduate of Magdalene.’ The Masters of Colleges had signed a decree that no undergraduate was to have any dealing with Mr. Wayman under a penalty of rustication, or immediate expulsion.

The lease then expired on Merton House and Wayman decided that he needed to actually own his own house, so he had built for himself Birnam House in Chaucer Road, at a cost of £5,000 (in 2009 the property belonged to Cambridge University and was valued at £3.5m). Here he really splashed out on servants, employing some nine in all, reputedly the best paid in Cambridge. He was also a town councillor for Castle End ward and was especially generous to the people there. As the newspaper said, ‘During his residence at Merton House Mr. Wayman was not only a generous entertainer of his friends, but he displayed great philanthropic tendencies, and was most lavish in his charities in the somewhat poverty stricken district of Castle End. By the poor people of the district Mr. Wayman was looked upon as a wealthy man, whose kindly disposition led him to give largely among those less fortunately circumstanced.’

Wayman’s bankruptcy was analysed by the newspaper as being largely down to his very careless record keeping. Added to this was his practise of repeated mortgaging of the same properties. These mortgages he then handed to clients as securities for monies entrusted to him. Thus a reckless transaction became fraudulent when it was discovered that these mortgages were effectively worthless.

In the end, Wayman seems to have completely disappeared. He abandoned his wife and was reported to have been seen in Spain by a University official. In 1899 the Cambridge Evening News published a reminder that it was eleven years since Wayman had ‘shook the dust of Cambridge off his feet … and he is so far as is known, still at large.’ It was only in 1900 that the final settlement with creditors was sorted. Wayman’s debts amounted to more than £79,000 of which creditors received just over 3d in the pound!

For further information and links to newspaper transcripts: