In Georgian times, the festive season started on the 6th of December (Saint Nicholas’ day) and finished on Twelfth Night (the evening preceding Epiphany). This meant that, at least for the middle classes and the aristocracy, there was during this period a flurry of social activities as clearly appears in James Nutter’s diary.

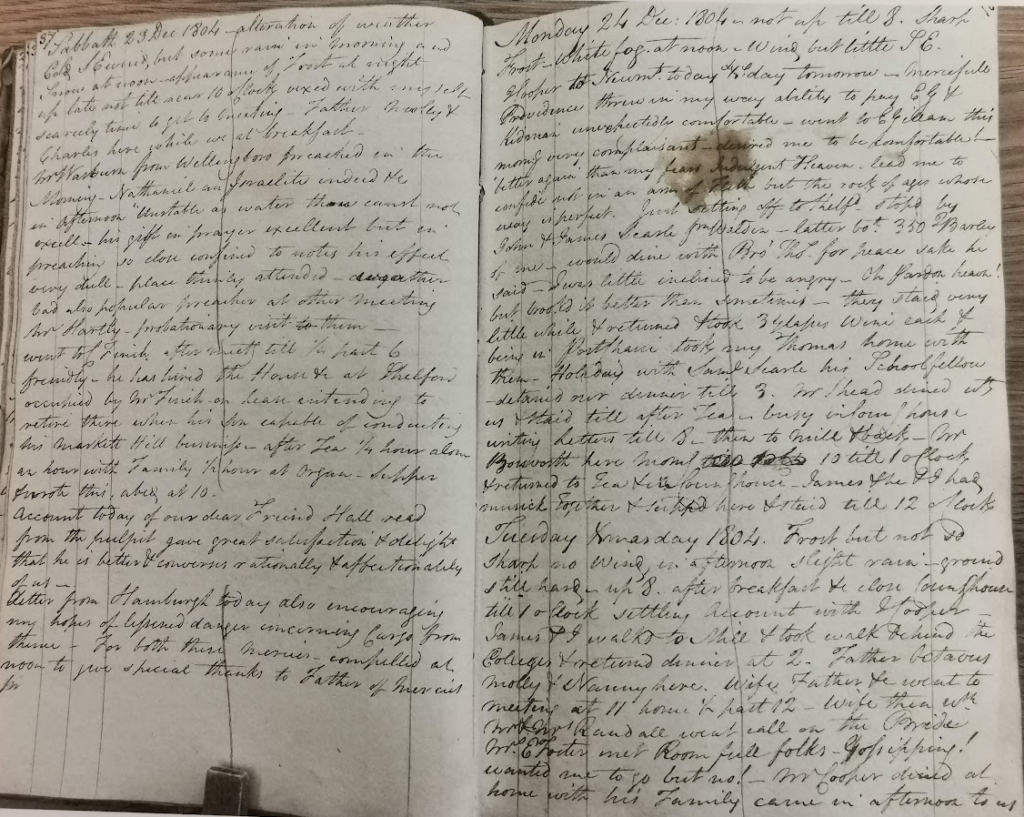

On Thursday 6th of December, Saint Nicholas’ day, James writes:

Day fine – morning frosty, ice on river – up 7 – T Cook off for Stortford London & Colchester to see his friends. J Cooper off to Ely & Mepal – I only home all day – close countinghouse. Morning & evening occurrences interrupted in middle day as usual- Wife sister Hannah Mrs Archer Eliza Anne Betsy gone dine Bridge not yet home now 1/2 past 8. James just home from post office & leave countinghouse.

Saint Nicholas’ day was probably as important as Christmas Day in Georgian times. James’ two employees, Cook and Cooper, seem to have been allowed to take the day off to see their friends and family. James’ wife Hannah, his sister Mary Gray from Saffron Walden, Mrs Archer and James’ older daughters, Hannah (18), Ann (12) and Betsy (10) have all been out the whole day. They had gone to eat with Thomas Nutter (James’ brother) and his family in his house on Bridge Street, a house which incidentally belonged to James and for which Thomas paid rent. The younger boys and girls stayed at home with the nanny. The eldest son, also called James, was fifteen at the time and was being trained by his father to take over the business. There is no time off for him! He spent the day in the countinghouse. The men in the Nutter family had very strong work ethics, probably from their Baptist background. The women, who are not expected to earn a living, enjoyed their time together and probably exchanging small gifts like the Georgians used to do on Saint Nicholas’ day. The fact that they went to “dine” (lunch) and were not yet back at half past eight probably shows how much fun they had. Friday the 7th of December was also socially very busy. The Nutter family had guests the whole day long, to “dine” (lunch), have tea and supper. “Abed 12 – wearied” wrote James (entry of 7th December). The Miller of Cambridge was obviously finding all the socialising rather tiring!

More enthusiasm was displayed in James’ entry for the 10th of December 1804 where he recalls attending the wedding of Charles Finch’s daughter, Elizabeth, with Ebenezer Foster (of the Foster bank). The two were married on the 10th of December at Saint Mary’s church, Cambridge, and then left the town to spend their honeymoon in London. “I had pleasure to hear the bells because twas the daughter of my friend” writes James. The diary entry also tells that James was sent some “bride cake” and a card which he glued in the diary and which is now missing (reason unknown). The marriage celebrated the union of two very successful Cambridge families, the Finches and the Fosters. Just as the old aristocracy used to marry within their own circle, the rising middle classes of the early nineteenth century tied knots with each other through marriages that strengthened their success and wealth. However, for Baptist families the choice was probably limited due to their religious identity that set them apart from the rest of society.

It is clear that Mrs Nutter had social aspirations as we learn, from an earlier diary of James, that she wanted to have one of the chief seats at church but was told off by her husband who did not want a conspicuous pew (see article by F. A Reeve). Maybe James, like many other “middlocrats” of the Georgian period, thought that “social rising was best done with sensitivity” (P. Corfield p. 272). As an intelligent and dedicated businessman, he was very aware of the uncertainties of middle class lifestyles. Bankruptcies were frequent and this was always at the back of his mind. In Georgian times, rising was just as quick as falling.

James Nutter had little desire to advance his social status by attending the fancy parties of the good and the great of nineteenth century Cambridge. However, like many middle class men of this period, he understood the importance of numeracy and literacy to sustain one’s economic transformation. On the 10th of December James wrote in his diary:

Carpenters began today put in new book cases each side of fireplace in parlour.

“Bibliomania” is one of the great features of the period, with people collecting, reading and reviewing books (P. Corfield p. 124). James was transforming his parlour, the room where guests were invited when visiting and dining, into a place of learning. On the shelves of the bookcases he would have, no doubt, proudly displayed the published sermons of Robert Hall, especially his sermon on Modern Infidelity Considered which was printed in 1800 and was the new “block buster” (P. Corfield, p. 49). This sermon was very much a lamentation on the weakening of traditional religious values.

Christmas Day 1804

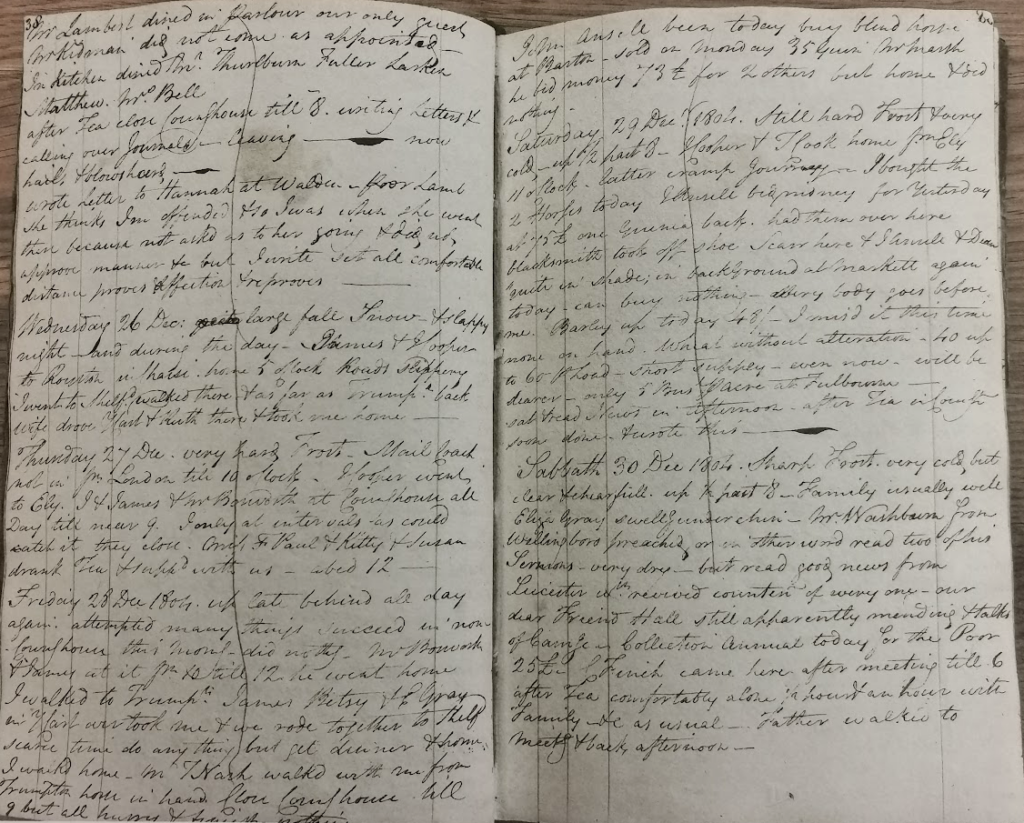

The parlour with its new bookcases was ready to receive its guests on Christmas Day. That day James got up at eight and goes to the countinghouse (the office) before taking a Christmas walk behind the colleges with his employees. He returns home for “dinner” (Christmas lunch) at two. Here was the rest of his diary entry for Christmas Day 1804:

Father Octavus Molly & Nanny here. Wife father etc went to meeting at 11 home 1/2 past 12. Wife then with Mr & Mrs Randall went call on the Bride Mrs E Foster met room full of folks – Gossiping! Wanted me to go but no! Mr Cooper dined at home with his family came in afternoon to us. Mr Lambert dined in Parlour our only guest – Mr Kidman did not come as appointed – In kitchen dined Mr Thurlburn Fuller Larker Matthew Mrs Bell.

After tea close countinghouse till 8. Writing letters & calling over journals – leaving – now hail & blow hard.

Wrote letter to Hannah at Walden – poor lamb she thinks I’m offended & so I was when she went there because not asked us to her going & didn’t approve manner etc but I write set all comfortable distance proves affection & reproves.

Christmas Day is clearly a family affair with James’ father in law and relatives going together to Saint Andrew’s church for the Christmas service (the “meeting”) before Christmas lunch. James’ wife also attends the big Christmas gathering organised by the Fosters after the service. The bride referred to is Elizabeth Foster who married Ebenezer on the 10th of December. Christmas weddings were quite common in Georgian times as this allowed an “all in one” big social event on Christmas Day as seems to be the case here. People did not have paid holidays back then and there was not much time to attend wedding receptions outside the Christmas period. James clearly disapproves of these kind of events: “Wanted me to go but no!” is a real cry from the heart of a man who dislikes gossiping and these kind of social events.

James’ puritan spirit may explain why his diary entry for Christmas Day is so sober. The family had lunch together in the parlour with just one extra guest. What did they eat? We will never know for sure. According to Maria Hubert, the most common meat eaten at Christmas during Georgian times was mutton that was enjoyed in front of a roaring fire. The fireplace in the Nutter parlour would have been glowing, standing proudly framed by the two new bookcases.

Did the Nutters have a Christmas tree in the parlour? Probably not as this is a custom that develops mostly during the Victorian period. However Mrs Nutter and the children might have decorated the house with green leaves and pretty paper curls as described in many of Jane Austen’s novels.

After Christmas lunch and tea, James goes back to the office to do more work. Feeding a family of nine children and employing five housekeeping staff (who have their Christmas lunch in the kitchen) is expensive and requires relentless work to keep afloat. James also spends time writing a letter to his eldest daughter Hannah who, without parental permission, went to spend Christmas with her aunt’s family (Mary Gray) in Saffron Walden. Maybe it was more fun there, maybe there were dances and games, maybe they played cards, Snap Dragon, Apple Bobbing and Bullet Pudding just like Fanny Austen did in 1804 (M Hubert p. 75). After all, James’ daughter Hannah was only eighteen years old. She was carefree and she wanted to have fun that Christmas in 1804!

Happy Christmas from James Nutter and family! The young Hannah especially wishes you a lot of fun this Christmas 2024!

PS: It did not snow on Christmas Day in 1804 but it did snow on the 26th of December that year: “quite large fall snow & sloppy night… roads slippery” (James’ diary entry)

References:

The unpublished diary of James Nutter, Miller of Cambridge, 1804-1806 (Nutter Family Archives)

The lost diary of James Nutter 1802-1803 as described in F. A. Reeve’s article “Problems which faced a local miller 150 years ago” Cambridge Daily News, 15 February 1962

Penelope J. Corfield, The Georgians, Yale University Press, 2022

Maria Hubert, Jane Austen’s Christmas: The Festive Season in Georgian England, The History Press, 1996

Appeal: Do you know what happened to the lost diary of James Nutter for the years 1802- 1803? Do you own the copy of it made by Mr Reeve? Please contact us via the Capturing Cambridge website to help us solve this mystery. Thank you.