Enid Porter may have been surprised with the resurgence of interest in home baking in the latter 20th century. In Cambridgeshire Customs and Folklore [1969], she recounts numerous culinary traditions associated with Cambridge, some attached to objects which are held in the Museum of Cambridge. We explore those traditions here.

Baking

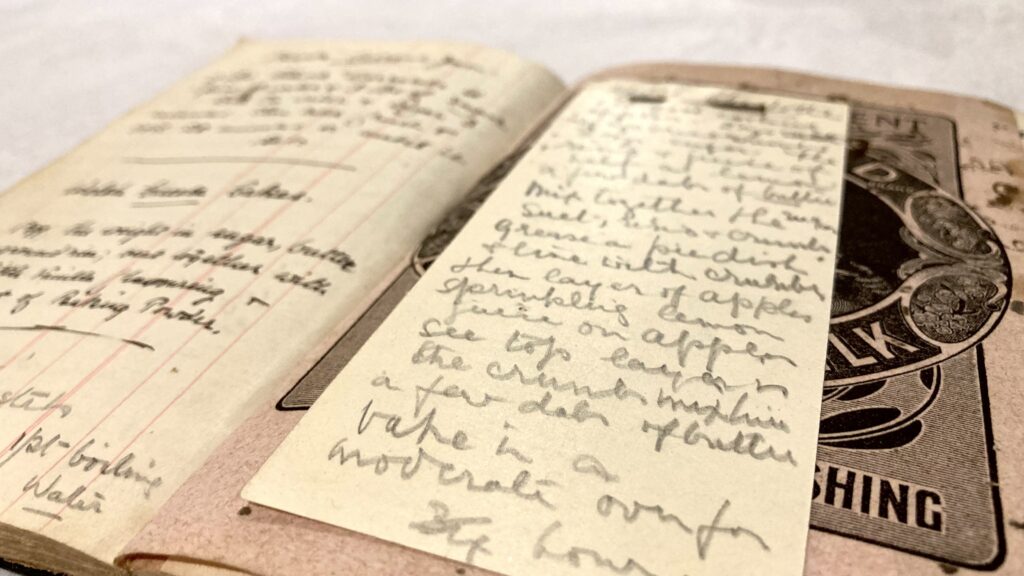

Porter writes of home-baking as an old tradition for which many Cambridgeshire farmhouses used a long wooden trough; one of these, 42 inches long, 18 inches wide and 34 inches deep, is held by the Museum. It was used weekly from the 1860s to the 1890s by a Grantchester woman, mother of thirteen. The raising agent most often used was liquid barm, the froth that forms on the top of fermenting malt.

It was also common for bakers to bake home-produced doughs, as well as Sunday dinners, Christmas poultry and cakes that were too large to go into small household ovens. Many recalled seeing housewives and children going round to the bakery after the Sunday morning service with white cloths to cover the newly baked foods.

Poor families might well have to survive on a water mess for breakfast and supper. A thick slice of bread as the base, sprinkled with pepper and salt and then hot water poured over. Milk could be used instead of water if it was available, and even a knob of butter.

Cheese

Until the 1930s Cottenham was famous for its cheese. Two varieties were made: a white Single Cottenham and a blue-veined Double Cottenham resembling Stilton. Cheese making was started there by a family who had come from Leicestershire where they had made Stilton and who tried the same recipes using local milk. There is also a record of a similar Stilton-type cheese being made in Soham. Cheese making in Cottenham went into decline after the enclosure of the land which had previously been used for about 1,500 cows.

There was a time when soft milk and cream cheeses known as Cambridge Cheese, Ely Cheese, or Cambridgeshire Cheese could be bought. By the mid-20th century production was confined to the Rathmore dairies in Sutton near Ely. The small straw mats on which they were sold used to be made by local cottages. When Cambridge cheese was broken up with a fork and pepper, salt, and vinegar were added, it could be served, with salad as ‘mock crab.’

Seafood

Production of eels in the Fens is well known. They would be boiled or cooked in pies. Edmund Carter in 1753 wrote that the fish days in Cambridge Market Place were Wednesdays and Fridays. Eels and jacks (young pike) were ‘extraordinarily cheap.’ Salmon and sturgeon would be found sometimes at the market. Oysters from Colchester would be sold between July 25th and April each year, especially during the time of Stourbridge Fair.

One of the strangest stories is that of the cod, caught off King’s Lynn and cut open in the Cambridge market in June 1626. A small book was found inside wrapped in canvas. It was taken, rebound and sent to the University Library. The following year it was reprinted under the title Vox Pisces or The Book Fish containing Three treatises which were found in the belly of A Cod-fish in Cambridge Market on Midsummer Eve last, Anno Domini 1636.

Vegetables

Diaries at the Museum of Cambridge recall the intensive production of lettuces, cucumbers, onions, and other vegetables in the Garden of Eden near Parker’s Piece. This area was later developed but the name has been perpetuated by streets such as Eden Street, Paradise Street, and Adam and Eve Row.

A well-known dish in the villages of south Cambridgeshire was Onion Clangers. They were made from suet crust, rolled out and spread with chopped onions and whatever meat was available. The whole was then rolled up and boiled in a cloth. Onion Puddings were popular, again, boiled in basins lined with suet and filled with onions and perhaps some meat or sausage.

Meat

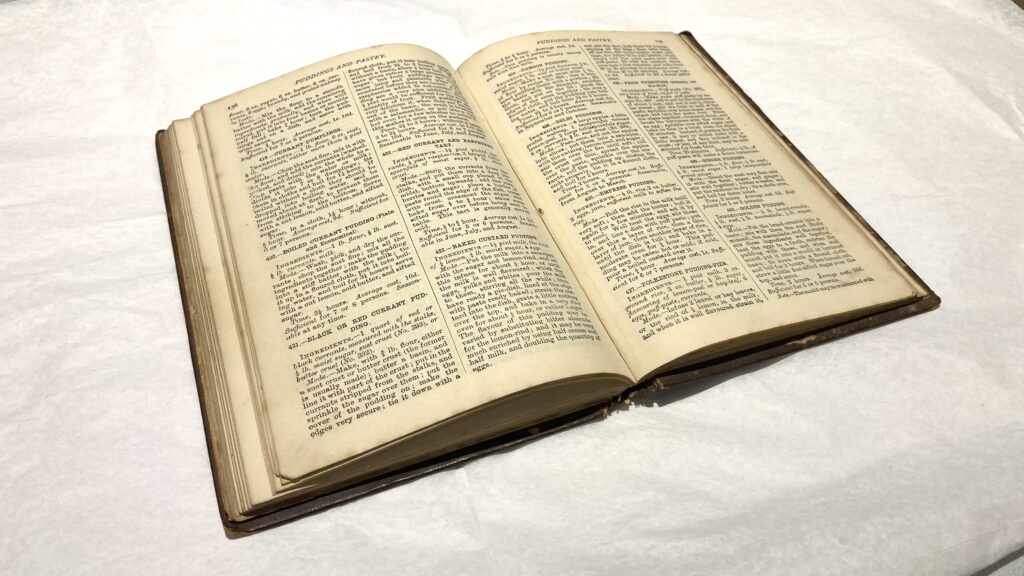

There is a recipe in Warne’s Model Cookery and Housekeeping book (1869) for Cambridge Sausage: 4oz beef, 4oz veal, 8oz pork, 8oz bacon, pepper, salt, sweet herbs and sage leaves. The editor writes that they are best eaten for breakfast. The donor of a small mincer and sausage filler to the museum in 1950 said that his father and grandfather had used the mincer in Swavesey to make sausages that they sold in the Cambridge market on Saturdays.

Other brands of sausage, such as Palethorpe’s Cambridge Sausages, were widely advertised. The high quality of the sausage production in college kitchens may have had something to do with local butchers going into production, as visitors to the city would often ask specifically for Cambridge sausages. The county was also a source of high-quality pork and some brands boasted of using pork meat alone.

Desserts and Drinks

There were no characteristic Cambridge desserts but amongst drinks, there were some recipes associated with Christmas festivities in the colleges. A recipe for Cambridge Milk Punch was published in 1856; the base was two quarts of milk flavored with lemon to which eggs, rum and brandy were added, whisked to a froth and served in glasses.

Tea was too expensive for poorer families in the 18th and early 19th centuries but after the price fell to 2s a pound from the 1860s, it became more popular. The cheapest sugar – brown, sticky, and lumpy – was used to sweeten it. Packets of tea would be offered as prizes at sports’ meetings. Gunpowder tea was especially popular and a pound of this, as well as a pair of shoes, formed the first prize in a young lads’ race held in Cambridge in 1838 to celebrate the coronation of Queen Victoria. The public notice (a copy of which is at the Museum of Cambridge) advertise the tea as:

Souchongacetameranchoorigdumfefafumrumpeecoeannuscoronatiomirabilis-flavoured

Cambridge was famous for its beer, and it was traditional to add it to Christmas puddings. Stingo, which used to be brewed in Cambridge, was often added. Many pubs would brew their beers on the premises; one of the last to do this was the Jolly Brewers in Milton. Villages would have their own Ale Conner whose job was to taste all the beers of the pubs in the village to check for quality. He would be paid 1s per visit. Over had its own Ale Conner as late as 1909.

This post was written by Roger, Trustee of the Museum of Cambridge

References:

Enid Porter, Cambridgeshire Customs and Folklore (Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, 1969).