There is little now to suggest that this narrow road in the heart of the parish of St Matthews, was, on the morning of 19th of June 1940, nine months after the start of the war, the site of the most serious civilian loss of life in the UK until that point in the war.

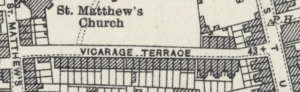

We know from the 1939 Register exactly who was living in the street; there were terraced houses along the southern side of the street, and a few on the north. The 1925 OS map shows the properties very clearly; the 1950 map shows a large gap at the western end of the street. This would in time become the Cherry Trees Day Centre.

Image (Upper): Vicarage Terrace, OS Map, 1925

Image (Lower): Vicarage Terrace, OS Map, 1950

A detailed account appeared in the Sunderland Daily Echo; censorship prevented it from naming the city but there is a list of the nine dead and ten injured. It had been an unusually clear night and the German bombers were believed to be targeting aerodromes in East Anglia. At this stage in the war, conditions were still challenging for defending British night fighters, but on this occasion one bomber had been brought down, the very first at night on British soil.

Diarist Jack Overhill who lived in Saxon Street wrote:

About 12.30 I was awakened by a terrific crash. I called the children down into our bedroom…. Then we heard gunfire. The crash turned out to be a bomb. (I heard at the bathing sheds tonight that there were two bombs, as they had discovered two craters on some houses in Vicarage Terrace….) the gunfire was from a Spitfire that went up from Duxford and brought down the machine that dropped the bombs…. I went and had a look at the damage done this morning. Nine houses were just a pile of rubble…. Later in the day the parson was there praying over the rubble.

Historian Michael Bowyer records the attack. He had been with his family in the bomb shelter next to Brunswick School when someone rushed in shouting ‘They’ve got Vicarage Terrace.’ He later discovered that a boy living at the Dog and Pheasant right next door, had rushed to Gwydir Street to get help. No-one would believe him, so the boy had to summon the police himself.

The modern numbering of the road has reversed the original order. All those killed and injured lived in nos 1-8, the Dear, Langley, Clark, Watts, Beresford, and Palmer families. The Unwin at no. 7 were very lucky; they had sheltered under the stairs and were protected from the collapse of their roof. Most did not take precautions and were buried in rubble. The one person not connected with the families listed in the 1939 census who was injured was Lily Itzcovitch, an eleven year old evacuee from London; she seems to have survived the war and married in London in 1946.

In the fog of war, rumours started to circulate. The bomber responsible had been shot down in Fulbourn; the German pilot had been a Cambridge undergraduate. Michael Bowyer recalls hearing all this as a boy but none of it turned out to be true. What did actually happen was that Olive Unwin, whose family had been sheltering under the stairs, went ahead with her marriage to Private George Brown just a few days later at St Matthews Church. She had to borrow a dress though; her wedding dress hadn’t survived.

This post was written by Roger Lilley, a Trustee at the Museum of Cambridge.