Lost in Cambridge!

Much of the action in Susanna Gregory’s novels about Matthew Bartholomew, the doctor from Michaelhouse College, set in 14th century Cambridge, revolves around Milne (Mill) Street.

If you wanted to retrace the route of Milne Street today you could start at its southernmost end, now the junction of Queens’ Lane and Silver Street. Queens’ Lane is the southern third of Milne Street. In Matthew’s day Queen’s College was yet to be founded (in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou.) Instead, the most prominent building would have been the Carmelite Friary, between the road and the river. These Whitefriars had moved to the centre of Cambridge at the end of the 13th century. Two hundred and fifty years later after the dissolution of the monasteries, Queens’ College took over the site. All that remains of the old Carmelite church is one wall, now the northern boundary of the college garden. A strange curiosity, though, survives from the time when the college had to subdivide the newly acquired Carmelite garden into four plots. The President of the college and the Fellows were not always on very good terms and had their own gardens so an ingenious building with four doors was created at the intersection of the four gardens which would enable passage from one garden to another without setting foot on any garden that was out of bounds. This ‘Four-door hut’ survives to this day and is featured on the Queens’ College website.

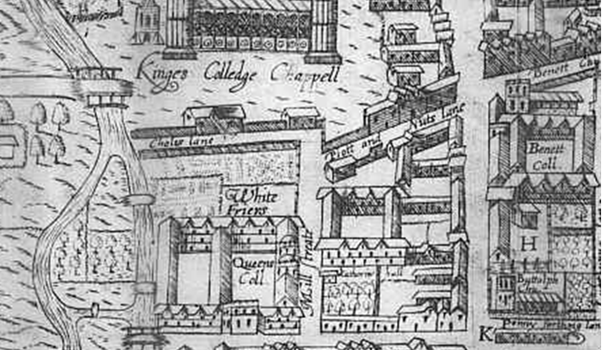

Richard Lyne’s 1574 map of Cambridge is the earliest that survives. Mill (Milne) Street is clearly marked north and south of King’s College. The central section of Milne Street disappeared when the King’s College site was developed in the 16th century. The riverside area here was transformed; at the time of Susanna Gregory’s novels it would have been the most populous part of Cambridge with docks, warehouses, and tiny houses. So busy that the debris produced in medieval times increased the ground level by two metres, according to Alison Taylor in ‘Cambridge: The Hidden History.’

The northern part of Milne Street is now Trinity Lane. Matthew Bartholomew would have seen, where the west end of King’s College is now, the church of St John Zachary. This was not only a parish church but served as chapel for the students of Clare and Trinity Halls, founded 1326 and 1350, respectively. The church would have been destroyed around 1446 when the foundation of King’s College chapel were laid. On the other side of Milne Street, where the east end of King’s chapel is now, there existed for a short while a college known as God’s House. It had been set up in 1437 in order to train school teachers. However, it found itself in the way of plans for the creation of King’s College chapel and so God’s House moved to a new location in 1448, and in 1505 was renamed, Christ’s College.

The north end of Milne Street met today what is now the southern boundary of Trinity College. Back in the 14th century this was the site of Michaelhouse, the second oldest college in the university. It had expanded by the gradual incorporation of private houses that had been hostels for student. One of these was Garrett hostel; its location was at the eastern end of Garrett Hostel Lane and Michaelhouse bought it in 1329. It was finally demolished in the 17th century. The lane in those days led down to Garrett Hostel Green, an island in the river.

The foundation of Trinity College in 1540 brought about the amalgamation of two colleges, Michaelhouse and King’s Hall, with seven further hostels, all under the new name. There had been a risk that these two colleges would go the way of the monasteries and have their assets confiscated by King Henry VIII, but the queen, Katherine Parr, managed to persuade the king otherwise and he set about the creation of his new college. Early pictures of Trinity College show that some of these original buildings survived but in due course most of Michaelhouse was dismantled and used for new buildings.

This post was written by Roger Lilley, a Trustee at the Museum of Cambridge.

The Museum of Cambridge is proud to present the Museum Making project, in which we are looking for ‘Community Curators’ to help shape the direction the museum takes in the future. If you would like to find out more, head to the Museum Making webpage.