The lives of Ion Keith-Falconer and Edward Conybeare

Recently, two important Cambridge cyclists have sparked my interest. The latest Boneshaker magazine, the magazine of the Veteran Cycle Club, featured an article about Ion Keith-Falconer (1856 – 1887) and we acquired a century old book, Rides round Cambridge by the Rev Edward Conybeare (John William Edward Coneybeare) (1843 – 1931). Both were early pioneers of cycling but in very different ways, one excelled as a racing cyclist and the other as an early pioneer of cycle rambles round the countryside. Their lives paralleled in many ways; both were public school educated and went to Trinity College, Cambridge, and both were committed Christians, Conybeare followed his forefathers into the church and Keith-Falconer chose missionary work.

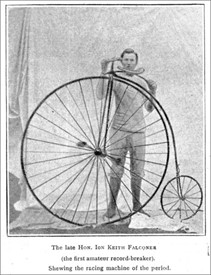

Ion Keith-Falconer in white.

Both photos courtesy of Wiki Commons

Bicycles were just becoming fashionable when Ion Keith-Falconer and Edward Conybeare began cycling. Keith Falconer’s enthusiasm started at Harrow school with a low velocipede and continued when he came up to Cambridge in 1873. As a tall and muscular aristocratic Scot of 6’ 3” (1.87m), he was a first class performer on an ‘ordinary’ or penny farthing bicycle. Such cycles were built to fit their riders and Keith-Falconer had the money to commission cycles with a large diameter to give him a competitive edge. He is credited with being one of the fastest cyclists in the world while at Cambridge and was celebrated as vice-president of the university’s bicycle club in June 1874.

In November of that year to wrote the following to his sister-in-law:

‘Yesterday was the ten-mile bicycle race. Three started. I was one. I ran the distance in 34 minutes, being the fastest time, amateur or professional, on record…… Today I am going to amuse the public by riding an 86-inch bicycle to Trumpington and back … It is great fun riding this leviathan: it creates such an extraordinary sensation among the old dons who happen to be passing.’

Further successes followed swiftly and in May 1878 he won the two mile National Cyclists Union championships to give him the (unofficial) world championship. He also excelled at long distance rides and in 1882 completed Land’s End to John o’Groats in 13 days which was no mean feat on bumpy 19th century roads when riding a primitive bicycle with poor braking power.

Keith-Falconer felt that rigours of 19th-century cycling were an excellent way of keeping young men on the straight and narrow. His early evangelism about cycling translated later into his Christian missionary work, first in Barnwell, Cambridge, then in London and later in Egypt and Aden. At Harrow School he had taught himself both Hebrew and Semitic languages. At Cambridge he furthered these studies and learnt Arabic, which he put to the test in Egypt. However, a visit proved unsuccessful and he returned to marry (1884) and become Professor of Arabic at Cambridge where he lived at 5 Salisbury Villas, Station Road. With evangelistic zeal, he and his wife moved to Aden in 1886 for a 6 month trial period. Sadly, within the 6 months he was dead from malaria. He certainly lived his short life to the full. As he said ‘I have but one candle of life to burn, and I would rather burn it out in a land filled with darkness than in a land flooded with light.’

In contrast, the Rev. Edward Conybeare had a long life with his wife and 5 children. His forebears were distinguished Anglican clerics, both Bishops, academics and writers. The work of his grandfather, the eminent geologist and palaeontologist, William Daniel Conybeare, is well known at the Museum of Zoology and at the Sedgwick Museum for it was he who first published papers on the marine fossils of both the plesiosaur and the ichthyosaur. Both museums have prized specimens among their fossil collections.

Courtesy of the Museum of Cambridge

After Eton, Edward Conybeare went to Trinity College and then into the church, first as a curate in Molesey, Surrey and then as vicar of Barrington from 1871-1898. He added Rural Dean of Barton to his duties from 1896-1898. By the time of the 1901 census he had moved into Cambridge where he lived at Stokeslea (formerly Lensfield .Cottage) in Union Road. In 1910 he became a Catholic and during WW1 was among other Catholics to help with Belgian refugees in the city.

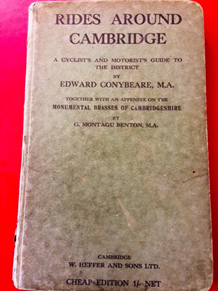

In the last few years of his ministry and after very many years of research and cycling, Conybeare started publishing books on history and the local area. Highways and Byways in Cambridge and Ely, History of Cambridgeshire and Rides round Cambridge are probably the most important for Cambridge folk.

Rides round Cambridge is a small volume, aptly sized to carry in a cyclist’s pocket. However the book is far more than just a details of the rides for it gives wonderful descriptions of the history of the roads, the villages and their churches. There are illustrations, maps and photos galore to add to the reader’s interest. The routes still seem well worth exploring and the book is worth reading for its history alone.

Did you know that the Huntingdon Road was part of the Via Devana, a cross- country Roman Road that ran from Colchester to Chester or that the chief reason for centuries-old Stourbridge Fair was to sell wool and cloth? Conybeare quotes Thomas Fuller’s History of the Worthies of England, published posthumously in 1662, as saying that fair started when traders from Kendal who were weather-bound in Cambridge on their way to sell cloth in Norwich, spread their goods on the common to dry. Interesting too is the fact that long before there was an official police force, the trading was kept under the watchful eye of special ‘constables’ in red coats.

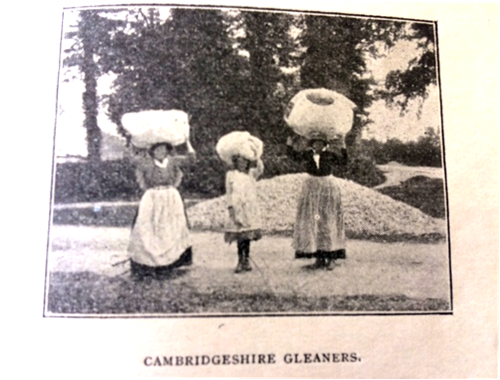

A century ago, the countryside would have been very different but the byways are still a cyclist’s heaven. I doubt though now we would see the gleaners in the fields at harvest time or hear the “Gleaning Bell’ from an ancient steeple. Can we still see 80 plus churches from Coploe Hill, the hill between Barrington and Haslingfield? The next time that I am in that direction I will make a count.

This post was written by Carolyn Ferguson, a volunteer at the Museum of Cambridge.

The Museum of Cambridge is proud to present the Museum Making project, in which are looking for ‘Community Curators’ to help shape the direction the museum takes in the future. If you would like to find out more, head to the Museum Making webpage.