‘We can all choose to seek out and celebrate women’s achievements.’

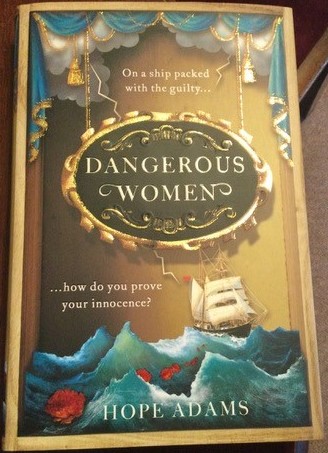

On March the 4th 2021, a local Cambridge author, Hope Adams, published her first historical novel entitled Dangerous Women. This novel, a murder mystery, takes place on board the boat Rajah which left London bound for Tasmania in April 1841 with 180 female convicts on board. While we must not forget that the book is fiction, some of the cast of female characters are real people and their considerable skills and achievements need formal recognition on International Women’s Day.

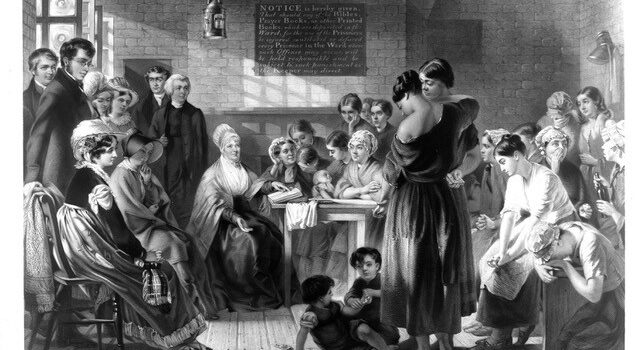

In April 1817, the Quaker and social reformer, Elizabeth Fry formed a committee of twelve ladies whose mutual purpose was improve the conditions for women prisoners, first in Newgate and then in other prisons throughout the UK. A year later their work was extended to include women convicts being transported to Australia. Fry was of the opinion that women in prisons needed skills for any rehabilitation to be successful and she and the ladies introduced sewing and knitting into gaols. A chance encounter with Captain, later Admiral, Young, gave Fry the idea that patchwork was useful both as a means of employment during the sea voyages and a way of teaching sewing. Thereafter each female convict was given a small bag containing a bible, 2 aprons, a cap, 2 pounds weight of patchwork pieces and various sewing notions. The patchwork pieces were deemed sufficient for each woman to make a quilt that could either be kept or sold in order to support their future life.

Besides the Captain and crew the ship’s company included ten children, a Royal Navy surgeon and a small number of passengers including a returning clergyman, and importantly the 23-year-old Kezia Hayter who was described as ‘a female of superior attainments’ in the Annual Report of the Ladies’ Society for 1842. Kezia was given free passage on the understanding that she should devote her time on the voyage to the care and improvement of the women prisoners.

Between April and July 1841 Kezia oversaw the making of large patchwork coverlet, approximately 3m square, now known as the Rajah Quilt, which is now in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. It is not known why Kezia wanted to travel to the other side of the world. We do know though that her father was dead and that she may have been estranged from her mother. She had met Fry and her ladies when working at Milbank Penitentiary and shared many of their religious sentiments and aspirations. It is assumed that the patchwork’s complex design was hers as she came from an artistic family; 3 of her relatives were painters at the Royal court.

The Rajah quilt is the only known remaining ‘convict’ patchwork to have been made on board ship. It is a terrific achievement when one considers the conditions under which it was stitched. Group quilts, in general, are difficult to achieve but one produced on the high seas, predominantly by convicts, is remarkable that it has survived. Although the voyage is well documented, we don’t know the actual names of the patchworkers. Research suggests that there may have been about 20 sets of hands at work. The complicated embroidery sections and inscription are thought to have been the work of Kezia herself. We must celebrate all these women and hope that they were some of the lucky ones who benefitted from life far from Britain. Kezia was certainly one of these for she fell in love with and married the Captain of the ship and had a fulfilled life down under.

Lastly we must recognise the work of the author, Hope Adams, who by bringing us a fascinating story, makes more people aware of the significant achievements of women at the start of the Victorian era.

I am grateful to The Library of the Religious Society of Friends for allowing me to reproduce the picture of Elizabeth Fry reading to prisoners at Newgate in 1816 from an engraving by Jerry Barrett, c.1860.

This post was written by Carolyn Ferguson, a volunteer at the Museum of Cambridge.